Uncovering the Giant Lizard Mystery: New Species Bolg Amondol Discovered in Utah

For two decades, the remains of a giant lizard that lived alongside dinosaurs were tucked away in a jar at the Natural History Museum of Utah. Simply labeled “lizard,” the fragmented and several millennia-old bones actually belonged to an entirely new species of giant lizard, Bolg amondol, which was recently discovered in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in southern Utah.

Bolg amondol was a raccoon-sized armored mostesaurian lizard that lived about 77 million years ago, similar to today’s Gila monsters (Heloderma horridum). The lizard is named after the goblin prince from The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien and was described in a study published on June 17 in the open-access journal Royal Society Open Science.

The living and fossil lizards in the Monstersauria clade are defined by their large size and distinctive features, including pitted, polygonal armor attached to their skulls and sharp, spire-like teeth. While these lizards have been on Earth for roughly 100 million years, their fossil record is largely incomplete. The discovery of this new species of Bolg is a step towards understanding more about these lizards, and Bolg would have been a formidable monster.

According to study co-author and paleontologist Hank Woolley, who found the unsuspecting glass jar at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles’ Dinosaur Institute, Bolg was “three feet tip to tail, maybe even bigger than that, depending on the length of the tail and torso.” By modern lizard standards, it was a very large animal, similar in size to a Savannah monitor lizard; something that you wouldn’t want to mess around with.

The discovery of this new species of monstersaur indicates that there were probably many more kinds of big lizards roaming the Earth during the Late Cretaceous – just before the dinosaurs went extinct. Bolg’s closest known relative, Gobiderma pulchrum, once stalked Asia’s Gobi Desert. While paleontologists have long known that dinosaurs traveled between the once connected continents during the Late Cretaceous Period, Bolg reveals that smaller animals made similar treks. This suggests common patterns of biogeography across land-dwelling vertebrates during this time.

The specimens in this study were first uncovered in 2005 in the Kaiparowits Formation of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This area overseen by the United States Bureau of Land Management has emerged as a paleontological hotspot over the past 25 years, producing dozens of new species. Discoveries like this underscore the importance of keeping public lands in the United States safe for future scientific research.

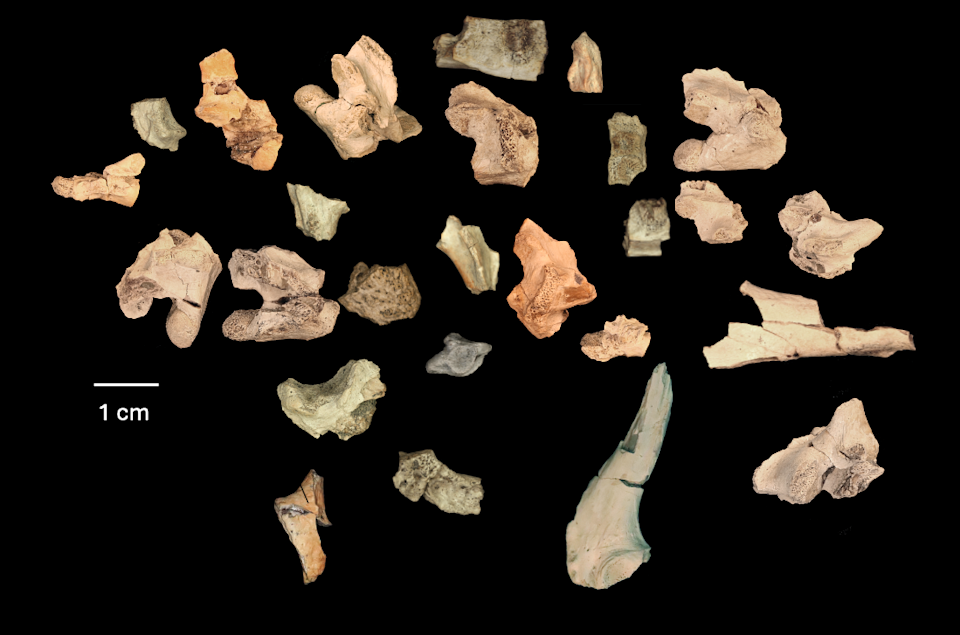

The team used tiny pieces of the skull, vertebrae, girdles, limbs, and bony armor called osteoderms to identify this new species. “What’s really interesting about this holotype specimen of Bolg is that it’s fragmentary, yes, but we have a broad sample of the skeleton preserved,” Woolley said. “There’s no overlapping bones – there’s not two left hip bones or anything like that. So we can be confident that these remains likely belonged to a single individual.”

The revelation of the new species Bolg Amondol in Utah, shedding light on the hidden giant lizard mystery is a transformative discovery that challenges our understanding and enhances conservation efforts for unknown giants. \

An astonishing discovery unveiled, the newly identified species Bolg Amondol of giants lizards in Utah challenges our knowledge boundaries with its extraordinary existence.