The Rise of Stablecoins: A Catalyst for a Monetary Revolution in the U.S. and Its Implications for the Global Financial Landscape

The financial landscape is on the brink of a monumental transformation that has been a century-long dream for many prominent economists. This revolution, driven by financial innovation, is taking shape as the U.S. political economy shifts to support it. The implications of this shift are vast, touching global finance, economic development, and geopolitics, and will undoubtedly create both winners and losers.

The Origins of Fractional Reserve Banking

Our current financial system is rooted in the concept of fractional-reserve banking, which emerged in the 13th and 14th centuries when Italian money changers began to realize that they could hold only a fraction of the coin needed to back their deposits due to the rarity of depositors demanding their money back simultaneously. This approach not only increased profitability but also facilitated payments across vast distances.

High Yield Savings Offers

While fractional reserve banking has been highly profitable and effective for payments in normal circumstances, it has a significant downside: its inherent leverage makes the system unstable. A downturn in the economy can cause more depositors to withdraw their savings simultaneously, leading to bank failures. When banks fail in a fractional reserve system, not only are depositors' wealth lost, but economic activity is severely constrained since payments for goods and services are impaired, and lending for new investment becomes unavailable.

Governments Attempt to Fix Its Problems

Over the centuries, as banks became more leveraged and critical to economic functioning, governments stepped in to try to reduce the risks of banking crises. In 1668, Sweden chartered the first central bank, the Riksbank, to lend to other banks experiencing runs. The Bank of England followed 26 years later. While this helped solve liquidity problems, it didn't stop solvency crises. The U.S. created deposit insurance in 1933 to help stop solvency-based bank runs, but neither deposit insurance nor bank capital regulations solved fractional reserve banking's endemic fragility. Government intervention reduced only the frequency of crises and shifted their costs from depositors to taxpayers.

Economists Build a Better Mousetrap

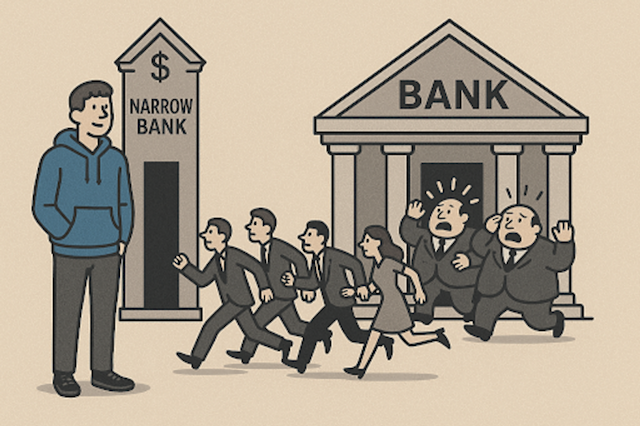

Around the time that the Roosevelt Administration was introducing deposit insurance, some of the era's top names in economics at the University of Chicago were hatching a different solution: the so-called Chicago Plan, or "narrow banking." The idea had a resurgence among economists during the U.S. savings and loan crisis of the 1980s and '90s.

Narrow banking solves the central problem of fractional reserve banking by separating the critical functions of payments and money creation from credit creation. Narrow banks that accept deposits and facilitate payments are required to back their deposits one for one with safe instruments like T-bills or central bank reserves. Lending is done by "broad" or "merchant" banks that fund themselves with equity capital or long-term bonds, hence aren't subject to runs.

This segmentation of banking makes each function safe from the others. Deposit runs are eliminated because they are fully backed by high-quality assets (as well as access to the central bank). Since narrow banks facilitate payments, their safety removes the risk to the payments system. Because money is no longer created by credit creation, bad lending decisions at merchant banks don't affect the money supply, deposits, or payments. Conversely, neither natural fluctuations in the economy's demand for money – booms or recessions – nor concerns over loan quality affect merchant banks' lending because it is funded with long-term debt and equity.

Why Didn't We Adopt This Wonderful Solution?

You may be asking yourself now, "If narrow banking is so wonderful, why don't we have it today?" The answer is twofold: the transition is painful and there has never been a political economy to support legislation to make the change.

Because narrow banking requires 100% backing of deposits by either T-bills or central bank reserves, the transition to narrow banking would require existing banks to either call in their loans, shrinking the money supply dramatically, or if they could find non-bank buyers, sell off their loan portfolios to buy short-term government paper. Both would precipitate a massive credit crunch, and the former would create liquidity shortages and payments problems.

As to the political economy, fractional reserve banking is extremely profitable – "a license to steal" as my father calls it (admiringly) – and generates a lot of jobs. Economists, in contrast, are a small group that are questionably employed themselves. Hence the continuance of fractional reserve banking is not a banking conspiracy; it's just been good politics and cautious economics.

Financial Innovation Meets Shifting Politics

That may no longer be so. Both the costs of transition and the political economy have changed, particularly in the U.S. Developments in decentralized finance – a.k.a. "DeFi" or "crypto" – and the coincident evolution of the U.S. political economy, national interests, and financial structure have generated conditions that make a shift to narrow banking in the U.S. not only feasible but increasingly likely in my view.

Stablecoins are decentralized "digital dollars" (or euros, yen, et cetera). Unlike central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) that are issued, cleared and settled centrally by central banks, stablecoins are privately created "digital tokens" (electronic records). The combination of blockchain immutability and universally replicated registries facilitates trust between unknown parties without a government guarantee. Stablecoins differ from cryptocurrencies in being pegged to fiat currencies or other stores of value that are more "stable" than bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. They were designed to be on- and off-ramps between the traditional world of fiat money and the blockchain-based world of DeFi and cryptocurrencies, and to provide a steady "on-blockchain" unit of account to facilitate DeFi trading. But stablecoins' use case has evolved significantly amid spectacular growth in acceptance and usage. Stablecoin annual transaction volumes through March totalled $35 trillion, more than doubling the prior 12-month period, while users have increased more than 50% to over 30 million, and the outstanding value of stablecoins has hit $250 billion.

With the Help of Congress

Stablecoins' increasingly rapid acceptance and growth as an alternative payments system is coming just as the Trump Administration and Congress are moving to institutionalize them. U.S. legislation defines what are acceptable high-quality, liquid assets (HQLA), mandates one-for-one backing and requires regular audits to establish compliance. Thus, Congress is creating the legal basis for entities that (1) take deposits; (2) are required to fully back deposits by HQLA; and (3) facilitate payments in the economy.

Shifting Political Sands

Both the Trump campaign's pivot to crypto last year and both houses of Congress moving to normalize stablecoins reflect a profound shift in America's domestic political economy and its sense of national interests. Bipartisan populist anger at banks and their relationship with Washington hasn't dissipated since the Global Financial Crisis. The Fed's QE and recent inflationary policy errors have only increased populist fury. This is just as much a part of the crypto phenomenon as FOMO (Fear Of Missing Out). But crypto also has generated immense new wealth and opportunities for business, creating a well-financed rival to the American Bankers Association (ABA). Even institutional asset managers now are diverging with their traditional allies in banking, salivating at the opportunities they see in DeFi. The combination of popular base and economic muscle is creating, for the first time, a political economy supportive of narrow banking.

And the New Financial Architecture

U.S. financial structure has become far more conducive to a non-disruptive transition relative to any time in its history or relative to other countries today, giving it an advantage over rivals. While the U.S. has long been less bank dependent for credit than other major economies due to its greater use of corporate bond markets and securitized mortgages, the growth of so-called "shadow" banking in the last two decades has made it even more so. Bank credit in the U.S. is little more than a third of total credit to the private non-financial sector. The rest is provided by bond markets and the shadow sector that are in fact the broad or merchant banks envisioned under the Chicago Plan.

The economic, geopolitical and financial implications of a shift to stablecoin-based narrow banking in the United States are huge. It would create significant winners and losers both within the U.S. and around the world.

The advent of stablecoins represents a potentially transformative catalyst for monetary innovation within the U.S., with far-reaching implications that could reshape global financial dynamics and challenge traditional systems worldwide.

An insightful examination into the rise of stablecoins as a catalyst for monetary revolution in America, presenting both opportunities and challenges that could redefine global finance.

The advent of stablecoins, with their unique potential to facilitate a monetary revolution in the US and beyond through increased financial inclusivity and reduced volatility across global markets #StabilityAsRevolution.

Stablecoins, with their rise in popularity and potential as a catalyst for monetary revolution within the US, pose an interesting dilemma that challenges traditional financial systems while offering new horizons of stability to global finance.