A Pride-Month Odyssey Through the Historic Gayborhood of Hell’s Kitchen

Photo: Gabby Jones/Bloomberg via Getty Images

More than a century ago, before rainbow-striped flags flew over restaurant patios and you could buy a Bentley on West 51st Street, Hell’s Kitchen was a crucible of struggle. This western swath of Manhattan—spanning 34th to 59th Street, Eighth Avenue to the Hudson River—began as an 1800s tenement district dominated by Irish-born railyard workers. Increasingly integrated by Southern Black migrants toward the turn of the 20th century, the neighborhood rapidly industrialized into a hub of factories and slaughterhouses, and became known for the kind of living conditions that kept typhoid top of mind. Irish ruffians of a certain bent found that organized crime offered an escape hatch—however problematic—giving rise to crews like the Gopher Gang and the Parlor Mob, who ruled the neighborhood’s saloons, bordellos, and gambling dens with fearsome tactics. Some days, they battled police; other days, they buddied up with them. In August 1900, white civilians and white cops rioted as one, unleashing two days of indiscriminate attacks against dozens of Black Hell’s Kitchen residents using lead pipes, guns, knives, fists, and billy clubs in what remains one of the largest explosions of racist violence in city history.

Today we chuckle over the goofy names of historic neighborhood gangsters like Stumpy Malarkey and Goo Goo Knox. Meanwhile, the names of Black men brutalized here fade into ye olde newspaper archives—men like Gordon Jones, Lloyd Lee, and John Lockett, whose face “was literally cut into ribbons.” Historians disagree on the 1800s origin of the Hell’s Kitchen nickname. Some say it was a scornful cop or local tavern owner; others credit Davy Crockett. But kudos to whomever did conceive the branding: Hell is where the trampled are forgotten. And if we don’t correct that, we too may be cooked.

The LGBTQ+ part of the Hell’s Kitchen story picks up, somewhat joltingly, in the 1970s disco era. Funky! Following a post-World War II immigration wave from Puerto Rico, in sashayed a small but freewheeling nightlife scene for LGBTQ+ folks at the margins: drag queens and dolls and gay hustlers drifting over from Times Square in search of safer, more discreet community spaces. (For context, this was when a majority of Americans still supported sodomy laws criminalizing gay sex.) It was these early queer arrivals who helped clear the way for an influx of white-collar gay men in the late 1990s, those who’d been forced to flee skyrocketing rent prices in Chelsea and the West Village. And thus, the Hell’s Kitchen gayborhood was born, with non-cis-heteros gaining status—after all that—as the dominant cultural force.

Only here we are, in June 2025, at risk once again of forgetting what came before. Stand on the northwest corner of 39th Street and Eighth Avenue, and you’ll find no trace that a queer hot spot called Escuelita once ruled the block. There’s no plaque explaining that it was one of the city’s longest-running LGBTQ+ nightclubs ever, or that the basement space (a former bowling alley) formed a vibrant refuge for the city’s queer Latino and Black communities. You’ll find no bronze statue of the club’s glamorous showgirls or G-string go-go boys, no mural depicting the legendary merengue balls that happened here from the late 1970s to 2016, no tribute to the trans women of color who were menaced by cops on the strip.

What you will find, however, is a Chipotle.

A haven for queer people of color owned by Savyon Zabar, Escuelita shuttered in 2016. Here, the club is pictured in 1990.Photo: Efrain Gonzalez

A haven for queer people of color owned by Savyon Zabar, Escuelita shuttered in 2016. Here, the club is pictured in 1990.Photo: Efrain GonzalezThis Pride season, one could say the white mobs have returned to Hell’s Kitchen, only this time as chino-clad vacationers lining up for mass-produced burritos. The arc of the urban universe often bends toward this kind of sanitized assimilation, according to historian and writer Marc Zinaman, author of Queer Happened Here, and sociologist Amin Ghaziani, PhD, two queer-identifying experts who provided crucial context for this article. It commonly happens this way: LGBTQ+ people populate a gritty district, fancy it up, and make it attractive for tourists and straight couples with 2.5 children, who then pave the way for Really Rich People. Before long, few can recall that the TD Bank was once a horny bathhouse.

The Hell’s Kitchen of today rattles with the construction cacophony of million-dollar micro apartments billed as residences, while real estate brokers undertake a genteel crusade to rechristen the area “Midtown West.” Now is when a neighborhood’s nervy queer energy generally starts to circle the sewers. Except wait: Hell’s Kitchen might not go down so easily.

When Ghaziani published the seminal book “There Goes the Gayborhood?” in 2014, an LGBTQ+ diaspora of sorts was under way. The American sociopolitical climate was feeling relatively accepting of gay stuff—call it the “Love wins” era, or the Target “Pride Collection” period. Many of Ghaziani’s LGBTQ+ interview subjects at the time expressed a feeling of freedom and possibility, a sense that they could happily live in lots of different places. No longer did they need “gay ghettoes” like the Village or San Francisco’s Castro district, which had helped buffer LGBTQ+ people from criminalization and social stigma after World War II and formed the backdrop of queer activist uprisings in the 1960s and ’70s.

To say the pendulum has swung back since the 2010s would be a crude understatement. The LGBTQ+ community—our trans members, especially—are facing a full-throttle retrenchment of rights, sadistic campaigns of erasure hatched at the highest levels of government. A staggering 729 anti-trans bills are pending across the country as of this writing. Since taking office in January, President Donald Trump has issued seven executive orders targeting LGBTQ+ people. For the year ended May 2025, GLAAD identified 932 anti-LGBTQ+ extremist incidents in the US, including 85 assaults, 20 bomb threats, 15 arson attempts, and 10 deaths. “Somehow, even same-sex marriage is back on the legislative table, which is kind of shocking,” says Ghaziani, also the author of Long Live Queer Nightlife and a professor of sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “I think what we’re starting to see as the world is flipping upside down is a rearticulation of needing each other once again, to respond to threats and hostility in a way that we have not seen in some time.”

What that means is, gayborhoods like Hell’s Kitchen could be poised to cycle back from being elective social spaces to something far more urgent. Ghaziani says, “In times of threat and hostility, where do we go to find each other—for safety, for comfort, for processing our grief, and also for organizing a response? Quite frequently, we go to gay neighborhoods and gay bars. When we need them, that’s precisely where we go.”

Vers, 714 Ninth Avenue, 7:00 p.m.

It’s Memorial Day weekend, and Vers bar is buzzing with pre-Pride month energy, which is to say it feels a little like Christmas Eve. Owner David DeParolesa finds me in the happy-hour crowd, grabs us a couple of seltzers, and squires me into a spacious booth. “Hi!” I say. “Hi!” he laughs. Three years into this venture and the magic still hasn’t waned. He’s doing it—fostering the sort of community he dreamed of as a lonely gay kid growing up in a rough part of Boston.

DeParolesa arrived in New York 16 years ago with just a suitcase, crashing with girlfriends on the Upper East Side. He discovered Hell’s Kitchen by wandering into it, crossing Sixth Avenue and Seventh Avenue and Broadway and then feeling the air shift. Unlike in some other city neighborhoods, no one here shouted homophobic slurs at him. He could breathe. He moved in and hasn’t looked back.

Opened in summer 2022 on Ninth Avenue between 48th and 49th, Vers aims to be a convivial, multipurpose space—a bar where you can party and grab a bite to eat and enjoy an actual conversation, like the one DeParolesa and I are having. A loungey ’80s-inflected interior by architectural designer Douglas Kane sets the mood, marking a deliberate departure from the grimy gay dives that dot the city. “Historically, those places were run by the Mafia, right?” DeParolesa says. “You got a black wall, you got a urinal, you got a plastic cup: Here’s your gay bar. Oh, and we’ll raid you every so often.”

Soon after VERS opened, the bar was targeted repeatedly by a vandal who threw bricks through the window. “Yeah, people were scared. But as is the case with queer communities, they come together during moments of strife, and people came out in droves [to support us],”says DeParolesa.Photo: Cole Saladino

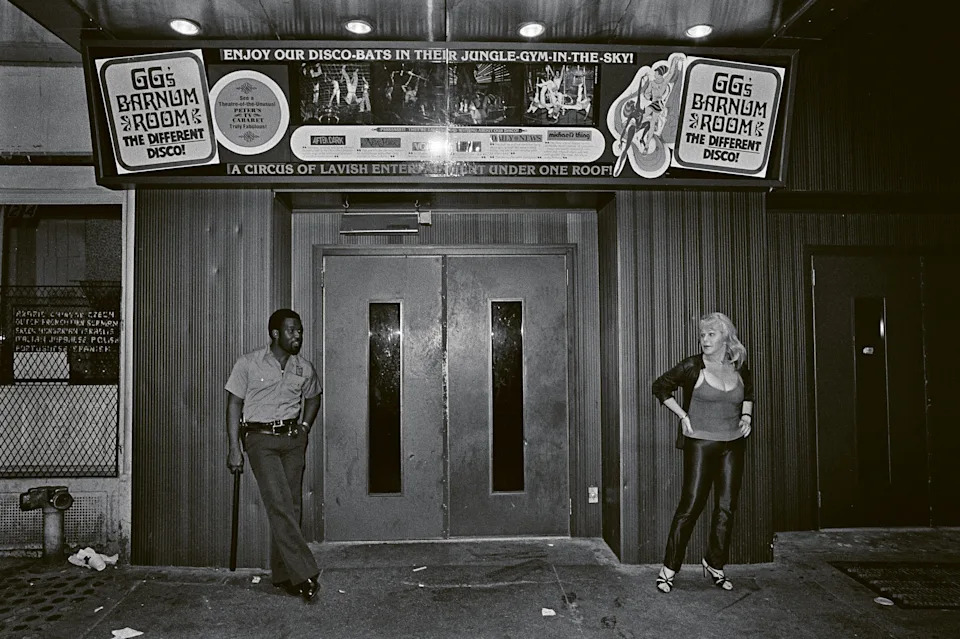

Soon after VERS opened, the bar was targeted repeatedly by a vandal who threw bricks through the window. “Yeah, people were scared. But as is the case with queer communities, they come together during moments of strife, and people came out in droves [to support us],”says DeParolesa.Photo: Cole SaladinoHistorian Marc Zinaman will later tell me that Mafia-run queer haunts hung on for a while in the Hell’s Kitchen area, yearsafter the 1969 Stonewall rebellion down in the Village. One of the last—and the one that may have burned brightest—was GG’s Barnum Room, a circus-inspired discotheque on the neighborhood’s periphery that was owned by associates of the Genovese crime family. “It had this trapeze netting that hung above the dance floor, and gay men and trans women of color performed as acrobats, doing movements while patrons danced underneath them,” Zinaman says. “There was probably some sex work happening there too; many in the trans community considered GG’s a safe space.” GG’s lasted just two years, from 1978 to 1980. Trans women may not have owned it, but for a blip, they made it theirs.

Before it was GG’s Barnum Room, this space on West 45th Street was the famed club Peppermint Lounge. That venue is credited as the birthplace of The Twist dance.Photo: © Bill Bernstein (Last Dance Archives)

Before it was GG’s Barnum Room, this space on West 45th Street was the famed club Peppermint Lounge. That venue is credited as the birthplace of The Twist dance.Photo: © Bill Bernstein (Last Dance Archives)DeParolesa is mindful of his place in history—and of New York’s position in the world. “Whatever you do here is propelled outside the walls of the city,” he says. So he’s also thinking of Vers as a politically conscious space. One of his favorite nights was a 2023 live benefit the team pulled together after Tennessee and Kentucky lawmakers initiated a crackdown on drag performances and gender-affirming care for trans youth. In just a few hours, Vers raised $7,000 for the ACLU and grassroots groups helping kids on the ground. That need is now greater than ever, following this month’s devastating Supreme Court ruling.

“I have a friend who works for the ACLU and he’s, like, ‘David, you don’t understand the privilege of being gay in New York.’ But I kind of do,” DeParolesa says. “What I’m hearing and what I’m feeling is that we’re still in positions of power enough to push where we need to push, and that the best thing we can do right now is support those who really need the help.”

New Alternatives, 410 West 40th Street, 3:30 p.m.

Kate Barnhart begins by telling me about her dad. At the headquarters of New Alternatives, the nonprofit Barnhart founded in 2008, I’m here to learn about the organization’s work in reducing homelessness among LGBTQ+ teens and young adults in the five boroughs, who make up a disproportionate 40% of the city’s unhoused youth population. That work is inextricable from Barnhart’s earliest experiences in the Hell’s Kitchen housing landscape, she tells me.

Barnhart’s father, a schoolteacher and occasional actor, lived most of his life in a fourth-floor co-op on West 55th Street between 10th and 11th. The building was one of several Hell’s Kitchen tenements the city had taken over, then renovated, then sold back to the original residents at a miraculous bargain. (Side note: A group of Hell’s Kitchen tenants are currently engaged in a similar push, working to secure ownership of two dilapidated buildings through a community land trust.)

Most of the residents were low-income. Many, like Barnhart’s dad, were LGBTQ+ theater types. As an ’80s kid—and queer herself—Barnhart saw and felt the positive impacts of affordable permanent housing: neighbors putting down real roots; the genesis of vital community. “Because of how it was to be queer at a certain point in time, these were people who didn’t necessarily have other families,” she says. When her father’s health declined, it was his neighbor of 50 years—a makeup artist named Charlie—who informed Barnhart her dad had been straying from his apartment late at night in a disoriented state. Charlie had even cooked her dad eggs and put him back to bed a few times. (Barnhart hired a live-in caretaker after that.) Eventually, her father was able to die in the home he loved. A young man who had grown up in the building stood in salute as paramedics took away the body.

Meaningful long-term relationships are a hallmark of the New Alternatives approach. Last year, Barnhart’s team held 693 individual case management sessions, helping clients one-on-one with everything from employment support to psychiatric crisis intervention. That’s on top of regular life skills workshops, HIV support groups, weekly free dinners, and fun outings like kayaking and museum trips. Twenty-one clients out of 287 total secured permanent housing in 2024, a major triumph. This year, the caseload has grown to include more young people from outside the city: trans teens bailing on the South and Midwest; migrant youth fleeing persecution in their home countries. “Both groups are really freaked out,” Barnhart says. The staff is working hard to provide political education, to adapt services for more languages. They’ve run drills on what to do if masked ICE agents show up. (Despite New York’s status as a “sanctuary city,” the Trump administration’s militarized mass-deportation blitz has hit local immigration courts, college campuses, apartment complexes, and more.)

Corporate and individual donations are down so far this year—another sign of the times. It’s unclear how long New Alternatives can hang on to its rented space in Metro Baptist Church. From her Pride-flag-adorned desk, Barnhart directs my eye to the room’s buckling windows. She describes how the building façade leaks and crumbles. The roof… Forget it. A proposed redevelopment plan for the nearby Port Authority bus terminal might pose additional structural hazards. In this market, moving might not be possible.

Some days are crushingly hard. “A lot of what we fought for for many years, including generations before us, is being taken away,” Barnhart says. “It’s really disturbing that we can’t offer people safety or even predict what might happen anymore.”

So the team zeroes in on their locus of control. Downstairs, a math tutoring session is underway. A yoga class will convene later tonight. Gloved kitchen volunteers stand over huge bowls, hand-mixing ingredients for meatballs. Sunday dinner service begins at 6:00.

Flex, 405 West 51st Street, 2:00 p.m.

Let it be known: Flex is a gay bar. It is a gay bar owned by gay men who seek to preserve and uplift gay culture. Co-owners James Healey and Jason Mann are telling me this in words. The neon lighting installation on the wall behind them—depicting a huge cock in money-shot mode—is telling me in inches.

The Hell’s Kitchen couple opened Flex two summers ago in the former home of Posh, a bar that helped define the neighborhood’s party culture for cis gay men, Zinaman notes in Queer Happened Here. After a quarter century of late-night ragers and community noise complaints, Posh shuttered in 2021, one of roughly nine LGBTQ+ bars in the area that did so during the depths of COVID. One former patron fondly told me about a time an upstairs tenant flung water balloons to disperse the rowdy crowd. (“It just added to the excitement and ridiculousness.”) RIP. For Healey and Mann, Posh’s closure was a lightbulb moment: This needs to remain a safe space for the LGBTQ community.

Gay Bars, Social Centers Of Queer Culture, Struggle To Survive Across NYC Amid Coronavirus Pandemic

Posh, photographed in 2020 before it closed the following year.Photo: Dia Dipasupil/Getty ImagesSo the first-time bar owners took over the spot with legacy in mind—if a slightly more mannered agenda. Their design team restored the beat-up brick walls, then meticulously renovated the space with an haute red-light-district aesthetic, drawing from the pair’s travels in Amsterdam and Berlin. The team also upgraded the building’s hundred-year-old gas and water lines, and scraped and cleaned the façade…possibly for the first time ever. The ceiling is now double-soundproofed, even though that meant sacrificing the original tiles. “We wanted the upstairs tenants to come enjoy the space and not go home and be miserable,” Healey says. “And so far, that’s been the case. The neighborhood’s been super great.” The two also own the Ben & Jerry’s next door, another balm.

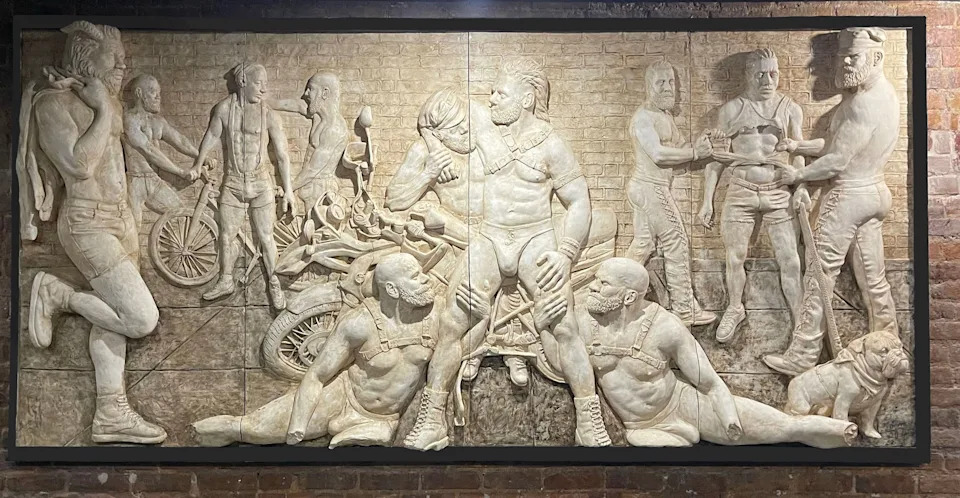

A sculpture featuring bartenders from a variety of NYC gay bars by artist Jo Mar adorns the wall at FLEX.Photo: James Healey

A sculpture featuring bartenders from a variety of NYC gay bars by artist Jo Mar adorns the wall at FLEX.Photo: James HealeyA low-relief wall sculpture by Colombian-born neighborhood artist Jo Mar pays splendorous tribute to a crew of gay male bartenders from New York City gay bars, repping present and bygone institutions such as Splash Bar and Boots & Saddle. The basis of the artwork? A shirtless group photo shoot. “Yeah, it was a fun day,” Healey says before I can ask.

Honoring their own makes sense in a world that seems intent on scrubbing queer culture from the public record. As Zinaman tells me, “Landmarking spaces generally has a lot of government involvement and politicking. The question of ‘What is a landmark?’ still isn’t defined.”

No matter: The Flex mural seems defined enough for me. I snap a pic and vow to remember.

Metropolitan Community Church of New York, 446 West 36th Street, noon

New York is a wild town. That’s all I can think as I sit in the stained-glass glow of Reverend Pat Bumgardner’s office at the Metropolitan Community Church of New York on West 36th Street. Is it possible that I am speaking with the pastor who personally ministered to Sylvia Rivera (1951–2002), the pioneering trans revolutionary who fought with heroic courage for people marginalized by the mainstream (white) gay rights movement? History really is everywhere, and so very close.

I’m not religious myself, but I do slip into a light devotional trance as Bumgardner describes how the spiritual alliance came about:

“I met Sylvia in a demonstration. We were marching to City Hall, and somehow, we ended up beside each other in the sea of people. She had been familiar with Troy Perry, who was the founder of Metropolitan Community Churches. So we started talking. I invited her to church. She was pretty anti-church. This would have been probably, like, late ’90s or 2000, something like that. But she came. She came one Sunday, and much to her surprise, I think, she got a standing ovation. People here, because of how we view the gospel as a radical social manifesto—that’s what it’s about—knew who she was and what she had done for us, and I think it kind of took her breath away, in a sense, surprised her. So she kept coming, and she was baptized here. There’s a picture of her in this long velvet cape; that’s how she dressed up for her baptism. It was on Epiphany Sunday. She looks like one of the Magi.”

I get why Rivera stuck around and ended up running the church’s food pantry: Rev. Pat is a baddie too. I come to learn she’s been holding it down for this LGBTQ-affirming Christian congregation for 44 years, 32 in Hell’s Kitchen. The church (part of a national fellowship) bought the building in 1993, when many members were still scared of the neighborhood. “My partner—my wife—sat out front in the car overnight just to see what happened on the street,” Bumgardner says. “And what we discovered was, it’s just people trading sex for survival.” She took her findings back to the church community: “It’s not a big deal. You’re safe. You’re fine.”

In this undated image (circa early 2000s) trans activist Sylvia Rivera works in the MCCNY kitchen.Courtesy of Les LaRue

In this undated image (circa early 2000s) trans activist Sylvia Rivera works in the MCCNY kitchen.Courtesy of Les LaRueThese days, she says, members are far more worried about resisting repression and bigotry. They’re looking to church leaders not just for guidance on how to cope but what to do—it’s just that kind of place. Bumgardner guides the flock toward tangible actions, things people can actually execute and show up for, such as letter-writing campaigns, local demonstrations like the upcoming Queer Liberation March, and support tasks for the church’s food pantry and emergency LGBTQ+ youth shelter, both of which are named for Rivera.

Reflection is helpful too, she says. “I encourage people to think more deeply about how Hell's Kitchen could be a center for what New York is supposed to be. Like, the center of the world, where everybody has a place, can get their needs met, and feels safe—not because there are 10,000 police on the street, but safe because we value diversity and want to build a realm where it’s possible to just be who you are.”

TMPL, 355 West 49th Street, 1:45 p.m.

After my meeting with Rev. Pat, I decide to check out the congregation at TMPL, a 49th Street gym unofficially known as the neighborhood’s gayest fitness outpost. Here, members pay $200 a month for a nightclubby ambience, spa-like locker room amenities, and classes with coy, heretical names like “Holy Water Resurrection,” which meets Wednesdays in the 25-meter saltwater pool.

Culture + Lifestyle

Lesbian Bars Are Back From the Brink

An uptick in the number of spaces for queer women holds promise for the future

CEO Patrick Walsh, who’s presided over the TMPL chainlet since acquiring it from fitness titan David Barton in 2017, has other business interests too—namely, as a key early investor in Donald Trump’s Truth Social platform, where the president has spent this Pride month fulminating against “radical left Democrats” maneuvering to destroy New York City through “Open Borders, Transgender for Everybody, and Men Playing in Women’s Sports.”

The muscled midday crowd streams through the TMPL entrance. I loiter on the curb rewatching Sylvia Rivera’s ferocious 1973 speech at the Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally, in which she excoriates New York’s gay “middle-class white club.” That club feels literal here, complete with a juice bar.

In a visibly queer neighborhood like this, it’s easy to assume everyone’s values are aligned, says four-year resident Connor Johnston, 32, an actor and writer originally from Oregon who video-chatted with me about his life as a proud “Hell’s Kitchen gay.”

“We don’t say too much about politics because it’s just…understood,” he intones. In the discussions he has had, he’s been surprised to learn where some people stand on Trump, or on Palestine. “It’s strange,” Johnston says uneasily, then jokes, “Should we do a wellness check? Maybe we should go around and be, like, ‘We’re all on the same page here…right?’”

Even though some threads unite the LGBTQ+ community, class is one factor that plays into political differences. And in this neighborhood—the same one abandoned by shady landlords during the citywide fiscal crisis and “white flight” exodus of the 1970s—median monthly rent climbed 8.3 percent year over year this past February to $4,550, outpacing the average Manhattan median rent increase of 6.4 percent. Meanwhile, median household income now hovers around $127,380, which is 60% more than the citywide median of $79,480. Hell’s Kitchen is about 50% white, according to recent population figures, about 20 percentage points whiter than New York City on average. Johnston, who is Asian, is often struck by the homogeneity at neighborhood parties and bars: Is anyone else clocking this?

In addition to more diversity, Johnston would love to see greater candor on these and other issues. Before even moving to Hell’s Kitchen, he commuted in regularly from Queens for volunteer shifts on the Trevor Project’s crisis hotline for LGBTQ+ youth, which, at the time, had a call center on 35th and 8th. In other words, sensitive conversations are kind of his specialty. (I too was a Trevor counselor.) Now that he lives here, Johnston has made dear friends within walking distance, plugged in with a local organizing group, and found the line between breezy belonging and social responsibility.

“It’s not like, ‘Okay, we did it. We made this area,’” Johnston says. He accepts that Hell’s Kitchen will always be a project.

“I love her,” he says. “I’ll never leave.”

Temporary encampment, 620 West 45th Street, 1:10 p.m. and 9:30 a.m.

As you head west through the neighborhood, Pride flags gradually give way to sweep notices—official warnings the city issues to unhoused community members seen camping on public property. In short: Move along or we’ll confiscate all your stuff. The notices are a stark reminder that high rent costs drive homelessness, which climbed 53.1 percent in New York State between January 2023 and January 2024. Ninety-three percent of that surge came from New York City. Enforced by police with varying levels of aggression, encampment sweeps are the subject of an ongoing federal lawsuit against the city, with homeless and formerly homeless plaintiffs alleging violations of constitutional protections against illegal search and seizure. And legal or not, many critics denounce the sweeps as cruel.

I chat with folks in a sidewalk encampment on West 45th Street between 11th and 12th who’ve been hit with a sweep notice for the following day. Soon, they’ll have to pack up everything in sight: clothing, personal documents, shelf-stable food items, tents, tarps, toiletries, blankets, umbrellas, books, some found objects (a vintage wall clock, a pair of subwoofer speakers) they could sell for cash later on. Then they’ll have to scope out other spots on which to set up and sleep—that is, until the next flurry of sweep notices appears. Street displacement in Hell’s Kitchen always ramps up during Pride season, they tell me, when business owners and partying visitors call in complaints to the city’s 311 hotline.

The New York City Police Department did not respond to an emailed request for comment on the timing of Hell’s Kitchen sweeps. Commenting by phone, Hell’s Kitchen City Council rep Erik Bottcher (D) tells me, “We don’t want the unhoused to be policed out of the neighborhood. Pride shouldn’t be an excuse to sweep anyone out. We do want people to get connected to housing resources and services, and that’s why we’ve been fighting to make sure that those are available.” By way of example, Bottcher cites a new 24-hour drop-in center on 52nd Street and 9th Avenue that provides case management, showers, hot meals, and more. Still, whatever the lattice of services, people continue to slip through.

An encampment resident named Andre McLeod says he’d like to speak on the record. He notices me admiring his fit: a short-sleeve button-up that shows off his toned biceps, a trucker hat that reads “King,” and layered silver necklaces that glint in the searing afternoon sun. “To look at me, you’d never know,” he says.

The Brooklyn-born 45-year-old explains he’s had a number of occupational seasons in his life and an often comfortable ride: star quarterback in college, a pro stint playing in Italy, a role as national youth athletics coach and scout, and a brush with acting and modeling. Eventually he followed the men in his family and pivoted to construction with a focus in transport infrastructure: the Kosciuszko Bridge replacement, the 7 subway line extension. He ran into some hardships along the way—drugs and such. When the work dried up, he came to Hell’s Kitchen, where he’s been on and off the streets for five years, using his trade skills to teach others how to tie down belongings securely, how to stack stuff on wheels for quicker escape—a convoy of wagons and rolling suitcases and granny carts.

The way McLeod tells it, Hell’s Kitchen underwent a weird vibe shift during the pandemic. People got sucked into simulated realities on Facebook, began living through their devices like in The Matrix. Sometimes, for fun, he’ll try to catch the eye of a stranger and toss out a few kind words as a pulse check: Yo, nice kicks! “People don’t even know how to take compliments,” he says. “No energy, no personality, like a foreign city.”

So he’s grateful for the connections he has made out here, his circle of fellow “urban campers,” at least two of whom are LGBTQ+. “Midtown is my home, y’know? And this is my family,” he says. “I genuinely care about people. I hope everyone makes it out.”

McLeod’s community also includes his hair stylist at Diamond Cuts Barber Shop on 40th and 8th; the old guy at the liquor store up the block; the neighbor in business attire who passes us across the street and catches this interview in progress.

“Hey, he’s a nice guy!” the neighbor calls out to me, gesturing toward McLeod. “He has lots of potential!”

McLeod laughs from inside the tent I’ll help take down the next morning, before the city can clear it away. “God bless!” he shouts back. “I know, man! I gotchu! ”

Originally Appeared on Architectural Digest

More Great Stories From AD

Not a subscriber? Join AD for print and digital access now.

Axel Vervoordt Crafts a Poetic Home in the Belgian Countryside For His Family

The 15 Best Places to Buy Bedding of All Kinds

What Makes a Space Gay? Unpacking Queer Interiors

A poignant and illuminating journey, 'The Pride Month Odyssey Through the Historic Gayborhood of Hell's Kitchen: A Tribute to Community & Perseverance,' explores a historic neighborhood with depth unmatched in celebrating its residents’ lived experiences.

A dynamically engaging narrative set to celebrate Pride Month, 'The Odyssey Through the Historic Gayborhood of Hell's Kitchen', re-trackers a journey through time with empathy and energy on that neighborhood where brotherly love came alive.

An engaging and enlightening odyssey, 'A Pride-Month Odessy Through the Historic Gayborhood of Hell's Kitchen', offers an insightful glimpse into New York City’S LGBTQ+ heritage while celebrating diversity with pride.

Exploring the historic Gayborhood of Hell's Kitchen during Pride Month offers a poignant and richly textured odyssey, illuminating not only its vibrancy but also attestifying to generations-old evolution amidst broader societal prideful coming out.

Exploring Hell's Kitchen during Pride Month is a vibrant adventure that takes readers through the historic gayborhood with all its color, energy and pride – an Odyssey of diversity celebrated in every corner.

A enthralling exploration tracing the path of pride through Hell's Kitchen, a historic gayborhood showcasing its resilience and rich heritage. This scholarship ignites discussions on identity preservation amidst revitalization.